P.J. O’Rourke also appeared today on NPR’s Talk of the Nation to talk about his new book about Adam Smith. If you missed it, no problem. You can listen to it for free on NPR’s website after 6:00 p.m. EST. (Thanks again to Chris for the tip.)

P.J. O’Rourke on NPR’s Talk of the Nation

January 8, 2007 | Permalink | Comments: None »

P.J. O’Rourke on C-SPAN II

December 29, 2006 | Permalink | Comments: None »

P.J. O’Rourke is scheduled to appear for three hours live on C-SPAN II, the public affairs cable channel, on January 7, 2007 at noon CST. (Start time not verified.) (Thanks to Chris for the tip.)

Chris Miller Interview on MrSkin.com

December 29, 2006 | Permalink | Comments: None »

There’s another Chris Miller interview over at MrSkin.com, a website devoted to nudity in films. Not a lot of overlap with the interview Chris did with me here, which is good.

Josh Karp on Young America

December 4, 2006 | Permalink | Comments: None »

An even better and lengthier interview with Josh Karp than the one on NPR can be heard on The Sound of Young America radio show website. It originally aired on November 17. Don’t miss the “bonus audio”—eight extra minutes that were cut from the broadcast (presumably) because it ran too long. Update: The recording appears to have been removed.

George W.S. Trow, R.I.P.

December 3, 2006 | Permalink | Comments: None »

George W.S. Trow, a frequent early contributing editor to National Lampoon, better known later as a critic of media and culture, has died at age 63. (Trow’s obituary in The New York Times.)

New Lampoon Movie?

November 27, 2006 | Permalink | Comments: None »

I’m told that a new movie is in the works, the first in a long time to be done by people actually associated with National Lampoon. The movie is to be called “National Lampoon‘s Dirty Movie.”

Josh Karp on NPR

November 20, 2006 | Permalink | Comments: None »

I don’t know how I missed this: Josh Karp, author of A Futile and Stupid Gesture, was interviewed on NPR back in September.

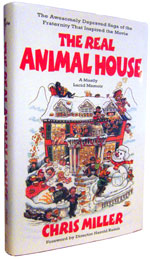

The Real Animal House

November 14, 2006 | Permalink | Comments: None »

is Chris Miller’s new book recounting his days in the Alpha Delta Phi fraternity at Dartmouth College in the early sixties. Several short stories about those experiences were published in National Lampoon in the early seventies and became, in part, the inspiration for the movie Animal House, one of the most popular comedy films of all time. The book is both less and more than the movie—they are really two separate stories with some common elements. One (the movie) is mostly fiction, and the other (Chris’s new book) mostly true. Chris’s book also goes far beyond what could be shown in a Hollywood movie. If you ever read any of the many short stories he wrote for National Lampoon, this will come as no surprise.

Yesterday, I spoke with Chris by phone:

Mark: Congratulations on the book. It seems to be doing pretty well. What’s been the reaction so far?

Chris: The reaction has been a real enthusiastic one because of the terrific review that was in The New York Times by Chris Buckley.

M: I read that. It was really very glowing.

C: I’ve hardly ever seen a review that was so one hundred percent positive on something. You could have knocked me over with a feather.

M: In the reviews I’ve seen, it seems like people either like it a lot or they don’t like it at all.

C: Maybe that’s just those speaking up, but that’s how people have always reacted to National Lampoon and to Animal House, and to that kind of humor. It got reviewed in the Dartmouth newspaper, and, oh boy, they panned it. Calling it shallow, and all it’s about is this that and the other thing and I don’t know. These people don’t get it. They’re too serious or something.

M: Yeah. There was a short review in Entertainment Weekly, and I wondered if the guy actually read the whole book.

C: I wondered that too and with the review from Kirkus. I had the strong feeling with the Kirkus review that they hadn’t read the whole thing.

M: Well, I would say that anyone who enjoys your short stories would enjoy the book.

C: Thank you. I think that anybody who enjoyed Animal House (the movie) would enjoy the book.

M: Definitely.

C: We got that great review and, immediately, you can see the reach of The New York Times because everybody starts buying it on Amazon. And by eight o’clock that night, we were number 26 on Amazon, five days after the book is released. So that was amazing. By now were down to 88 or something because I guess you have to keep doing publicity for these things. Tomorrow, in fact, I’m on Bill O’Reilly’s show, The O’Reilly Factor, of all things. [Note: Chris’s appearance on O’Reilly’s was postponed until Monday, Nov. 20.–MS]

M: Wow. Well, good luck with that.

C: Bill is an Animal House fan, I’m told. And he requested that I be on the show. Hopefully, he’s not planning to torpedo me with God-fearing, traditional American kinds of carps about my book, but you never know.

M: Why did you decide to write the book now? Is is something that’s been brewing a while?

C: Well, Mark, I actually started this thing in ’73. Writing short stories for National Lampoon was all very well, but I wanted to try something longer. But after writing three chapters, I kind of lost my forward motion on it and went back to writing my short stories. One month I couldn’t think of one. So I pulled one of those chapters out of the drawer. It was “The Night of the Seven Fires.” So it ran in the magazine and that triggered Animal House.

So, I kind of forgot about this book I was going to write. But, two things struck me.

The first was I had originally wanted to tell the story of a group of people in this elite school, people who, when they leave Dartmouth, they go out and run the world, basically. They’re your doctor, your judge, your congressman. What amazed me when it was happening in the early sixties was that, these people, who were gonna go out and be the upper crust of the world, were doing these incredible acts of depravity. By the way, it’s nice depravity, okay? But depravity. I was so mind-blown by it all that I felt that I wanted to share that information with the rest of the world. People just would be amazed. Animal House didn’t do that. Animal House told the story of a generic American college and the adventures there on of a crazy fraternity and their fascist antagonists. And that’s great, but that’s not story I was originally telling.

The other reason was that these events were forty, forty-five years in the past. Enough time had gone by that they could be viewed over that distance and start to be like myths, that I could consciously try to make a story of sort of mythic fraternity pranksters, and furthermore that most of the guys that were involved probably wouldn’t give a damn anymore if I put these things in the book.

So, all of those things came together. Plus I needed some dough. It was 2002 when I decided I was going to move ahead on it. So, I got an agent and we sold the book to Little Brown, and I wrote it for two years and here it is.

M: And you got Rick Meyerowitz, who did the movie poster illustration, to do the cover, too.

C: Yes, absolutely.

M: I think it’ll be good for the book.

C: I think it’s a great thing. (And, if you’re curious, Rick is doing just fine, thanks.)

M: Did the response to the Animal House movie surprise you? Did you expect it to be such a success?

C: It was a bigger hit than we expected. I was naive enough about the film business to think that I could predict it would be a hit, which of course is normally not possible. The three writers, Doug Kenney, Harold Ramis, and I, thought we had done a hell of a script and that we were gonna have a hit movie. But nobody thought it was gonna become an iconic movie that would become clasped to America’s bosom as some kind of quintessential American story. Nobody expected that. Not a day goes by when I don’t hear a line from Animal House used in some other context, or see an article in a newspaper where they’re referring to someone as an Animal House kind of guy, or referring to the Republicans as Omegas… Nobody could have predicted that. And I still am pretty amazed, to tell you the truth.

M: Getting back to the book, when I got to the end of it I had a weird thought. It made me think of the Harry Potter books.

C: How interesting.

M: Here’s this guy, he doesn’t fit in at home, he goes off to this school where he joins a legendary house, he learns how to do all sorts of tricks with his wand, and then has all kinds of exciting adventures with his new-found friends. Except there’s beer and sex instead of magic.

C: Yeah. That’s terribly interesting. I would never have thought of that. I’ve only read one of the books.

M: Well, each book covers a year at school. And I realized at the end that that’s what your book does also. They’re both kind of part of that “school book” tradition.

C: Yeah, you’re right.

M: It’s kind of tenuous connection but it just struck me.

C: Well I love hearing that. Have you heard of or read much of Jean Shepherd?

M: Yeah, a little bit.

C: My publisher, Michael Peach, says he thinks this is like Jean Shepherd. Which was very flattering to me because Shepherd was a hero of mine. One of my story-telling heroes. He could tell a story better than anyone.

M: Didn’t they have something of his in Lampoon once?

C: I don’t know…

M: Yeah, I think there was one story they ran of his. In the early years.

C: That’s possible. A lot of people showed up in the Lampoon. Terry Southern showed up there once or twice. I didn’t remember that Jean Shepherd did, but that’s cool.

M: One thing I noticed, too, in the book there are these essays that the pledges are required to write as part of getting into the Alpha Delta house. And it seemed to be kind of a precursor to your Lampoon short stories.

C: [laughs] Well, maybe that’s where the seed was planted.

M: I can see glimpses of some of your short stories throughout the book. Nuggets, maybe seeds of things to come.

C: Well, I certainly felt free to pirate characters and situations for some of the short stories, because they were always autobiographical anyway. [laughs] But, yeah, maybe it all started with “Three Good Ways to Cut off a Girl’s Nipple” that’s lead to my current position at the heights of the literary stratosphere. [laughs]

M: One of the pledges had to write a story about finger painting with shit.

C: Yeah, that I consciously took for one of my stories. [The Toilet Papers, September 1971]

M: You also write about how you read a lot of science fiction when you were a kid. And that shows up in your stories, too. In fact, those are some of my favorites.

C: Thanks. Yeah, one of my favorite moments was when I saw my name in the table of contents for the Lampoon‘s Science Fiction issue [June 1972] right next to the name of Theodore Sturgeon, another writer hero of mine. I thought that was cool as shit.

M: Yeah, those stories blew me away.

C: How about the one called “Practice Makes”? That was very science fiction. This guy is trying to make time with this girl at a party and he keeps blowing it and–oop!–he’s starting over and doing it again, and–oop!–he’s doing it again. Remember that one?

M: Oh, yeah.

C: And it winds up he’s in the future and he’s part of something called a “tri-therapy group” with these two chicks and everything. I took that structure from a Philip K. Dick novel.

M: Ah! I’m a big Philip Dick fan.

C: Oh! Are you? Oh, boy, I loved every book he wrote. That idea was from one of his called “A Maze of Death”.

M: Maybe the reason I got into Philip Dick was from reading your stories.

C: Yeah, maybe. No room for science fiction in a fraternity house, unfortunately.

M: It didn’t sound like it.

C: I couldn’t find a way to work in a time trip or anything.

M: I read somewhere that the people who did Back to the Future got the idea for that from one of your stories.

C: Sure, “Remembering Mama.” It was a situation in which a guy, in order to protect his own continuing existence, has to force his father to continue fucking his mother, to make sure he gets conceived. And they did do that in Back to the Future. My jaw kind of dropped when I saw the movie. Then later, I was talking to a screenwriter friend, who was friends with the guys who wrote that movie, and told me that they had told him at some point that they dug my writing, and that they were big fans. So I went Uh-Oh-Ooh-Ah! [laughs] I even looked into things like legal action once or twice. But out here in Hollywood, what seems to boil down to is, you can do it, but if you do it, you’ll never work in this town again. So, I just didn’t do it.

You know, Duke Ellington had a good approach to this stuff. Around 1948 or so, some R&B guy took one of his melodies. Song goes out and it’s Duke’s tune, but turned it into an R&B instrumental. And people said, “Duke! Aren’t you pissed off? Aren’t you gonna slap him down?” Duke said, “Nah, nah, we all borrow from each other all the time. What’s the big deal, man?” Brushed it off. I thought that was a pretty good attitude, and I try to take that attitude when things crop up like that.

M: Yeah, I would agree with that. I noticed that there were a lot of musical references in the book. I especially enjoyed your description of the John Coltrane show.

C: Oh, thank you.

M: It sounded like the place to be at that moment in time.

C: I was talking to somebody last night about how lucky my generation is musically to have come along just when we did. We got to hear rock and roll from the beginning, from ’54. We got to hear a period in Jazz which was just unparalleled, with giants like Coltrane and Miles Davis and Charles Mingus and Thelonious Monk. We didn’t know how lucky we were. We just thought, there’s always great music because the whole time we’d been around there was great music. Only later did we discover that that was a time of enormous musical energy, and it’s not always like that.

M: How did you start writing for National Lampoon?

C: I had been at an ad agency, and I left. And with the money I got when I left, I spent some time not working, hitchhiking around. I went to Mexico and stuff. And when all that was done, I came home and looked at my bank account and said, oh my god. I’ve got maybe six months left of rent here. I’d better do something. I was too naive to know that if you need money, you don’t try to write short stories to make a living. Once upon a time, you could make a living off of those things, and your literary agent would sell them to magazines for you.

M: Like to Colliers, or all those magazines back in the thirties…

C: Right, Saturday Evening Post, all those magazines. And science fiction–my god. In the 1950s–especially in the early to mid 1950s–there must have been twenty science fiction magazines a month. And they were mainly short stories or novelettes. But their time had gone. I didn’t know that. So I sat down and started writing short stories and mailing them off and got rejected everywhere. I’d even sent them to Lampoon, who hadn’t even bothered to get in touch with me to reject them.

I was getting real close to having to crawl back to my old advertising agency and beg for a job when a phone call occurred during which a bunch of editors at the Lampoon and a bunch of editors at Playboy just sort of had a long chat one day on a group call. Somebody from Playboy mentioned me. It turned out that at Playboy my stories had made a huge impact. The editors there had loved them and wanted them to be in the magazine. But Hefner said no. They weren’t to Hefner’s taste. For him, they weren’t funny. So they were saying, but you guys at the Lampoon, these would be right up your alley. And the Lampoon guys were going, Miller… Miller… who was that? And they went to the filing cabinets where they dumped all the unsolicited manuscripts without reading them. Somebody remembered my name for some reason and they found it in there and the brought it out and read it. The next thing I got a call from Doug Kenney saying, please come up to the magazine. And I came up and he welcomed me like a long lost brother. And that’s what happened. I started putting something in as often as I could crack one out.

M: Wow, that’s great. I’ve never heard the whole story before. For a while it seemed like you had something in every other issue at least.

C: Yeah, maybe eight or nine times a year. By the way, Mark, my next book is going to be a collection of what I think are the best of my short stories.

M: Really? I was going to ask about that.

C: Right, I have a two book deal with Little Brown and the second book is to be a collection of short stories. The only question is when it’s going to come out. I’m thinking, now that the Reall Animal House book is doing well, that it’s going to come out sooner rather than later. Particularly because I cleverly left out that story that was once in the Lampoon called “Good Sport”–do you remember the one? It’s the one in which the boys have a beat-off contest in the fraternity house. I was originally going to put it in the book. And then I said, well, wait a minute. Let me hold this back as a short story. Then the people who loved the Real Animal House book will be interested in this book of short stories, and then they’ll get to read my other short stories. So, that’s what we’re gonna do. That chapter will be featured in the book.

M: Well, that’s great because that’s one of the questions I had for you–to ask if you ever considered publishing a collection of your short stories. The question comes up pretty regularly from people who read my site.

C: It seems to have eluded me for years and years. In order to get it to happen, I needed to write something new. So I finally got around to doing that, and it seems to have done the trick. I’m thrilled because I too have wanted my short stories to be published as a collection for a long long time.

M: Well, that’s great news. I’m sure a lot of people will be happy to hear about it.

C: Not as happy as I am.

M: Because, really, there’s nothing. People ask and I tell them, well there are a couple paperbacks that have, like, four or six of them in there, you know?

C: Yeah, there was one thing called “A Dirty Book”, which had a bunch of them.

M: But that’s about it.

C: I’m thinking about writing a little page and a half intro to each thing, about what was going on, maybe an anecdote or something up at the Lampoon, or what the story turned out ultimately to mean to me.

M: Sure, yeah. Definitely.

C: Because when I wrote a story, my mind would be on the surface events of the story and I had no idea what it was truly about underneath. To give you an example, that story, “Boxed In.” I wrote that whole story, finished it, and three days later realized it was about the relationship I was in, that I was feeling trapped and needed to get the hell out of it. So I did [laughs].

M: I think it would be a good idea. Especially now, it’s been so long since those stories were written, people will need some context anyway.

C: Yeah. You’re right. For instance, for “Telejester” I might need to say a couple of things about Watergate. The glee of the satirists at Lampoon at the time.

M: I think that was the first story of yours I read. It was the first issue I bought and you had a story in it. And that was it. I always liked that story.

C: That’s nice to hear, man. I’ve had very little contact with my fans over the years. I now have a website—chrismillerwriter.com.

M: Great. Let’s talk about the Real Animal House book some more.

C: I think the thing about the book is this. As unlikely as it may often seem, most of the stuff in it is true. You couldn’t make that stuff up. Maybe details have been changed. Or I’ve given a story a different ending because it would be funnier that way. The actual thing itself, whether we’re talking about brains in a glass or taking a shit in the mouth of a snow statue, that’s real stuff. [laughs] And Animal House, for all its rowdiness, is a Hollywood movie. There was stuff that just couldn’t be in there. Luckily, the literary world is more tolerant.

M: I definitely got the sense that it was stuff that couldn’t have been made up. [laughs]

C: [laughs] “The Night of the Seven Fires” by itself was quite a story. Did you like the longer version?

M: Yeah. I was going to ask you, it seems like there were some differences between the story in the magazine and the chapter in the book.

C: Sure. Stew the Jew disappeared because I found out he hated being called that. So, I just eliminated him. Yeah, I don’t know what all changed. After a while it all runs together in your head. Otter was still the same way, pretty much. I didn’t have the hot dog fly out of the guy’s ass and knocking the character out, because that’s not believable. A cartoon moment.

M: [laughs] Right. That was in the original story.

C: Right. So I went to something in the book that was much, much closer to what really happened. Seemed like a good idea in 1974 to write it with the hot dog flying out his ass.

M: Yeah. When I read the story back then, it didn’t even occur to me that any of it was true, it was so crazy. I didn’t know at the time that it was based on something that actually happened. Then, after the movie was made, I read somewhere that those stories really happened. And it’s not the same story you see in the movie, either.

C: Yeah. Some of those cranky reviews have said, well, there’s no Dean Wormer here. They don’t have any rivals or antagonists. Well, yeah, we didn’t. It’s supposed to be a memoir about what really happened, pretty much. I guess you probably read in the preface, I found a way to give these guys credible deniability if somebody tracks them down. I heard about how in a firing squad they leave one rifle with a blank in it so that any one of the guys might have been the one that didn’t shoot the guy. So, all of my fraternity brothers might have been in the two stories that were made up. [laughs] We’ll see if that gets anybody off any hooks or if I’m just being too careful. But I didn’t want anybody’s real names to go in there. Just nicknames.

M: And your stories were not the only ones used in the movie. There’s also Doug Kenney’s stuff, like form his “First Lay Comics,” “First High Comics,” ….

C: Plus the High School Yearbook Parody.

In Tony Hendra’s book, Going Too Far, I was fascinated by what he wrote about Animal House. He did like sixteen pages on it and called it the absolute culmination of Lampoon humor, as opposed to Saturday Night Live, which he thought of as sell-out humor. Of course, I enjoyed reading that and totally agreed with him. But I found it to be a fascinating analysis of the movie. That most people are just too busy talking about all the crazy stuff in it, and maybe a couple mention that it’s a subversive anti-authority kind of movie.

M: I think he made a point about how there was this spate of imitation Animal House movies, like Porky’s, that had all the gross-out humor, but without the satire.

C: Right, and the anti-fascist subtext. [laughs]

M: “Hey, look! A movie about partying! Cool. Let’s do a party movie!”

C: We had to figure that out, too. I remember when Doug Kenney and I were out there on the first day of shooting, and some rather serious looking reporter said, “What’s the theme of your movie?” Doug and I looked at each other. We shrugged and said, “Fun is good.” And that was what we were thinking the movie was about then. But now, I think it’s about the battle in every human heart between the forces of the super-ego and the forces of the id. That’s why everybody can relate to it, because we, all of us, have that battle that we see between the Delta ids and the Omega/Dean Wormer super-ego characters. Every human soul has to deal with that. And for once, the id wins!

You know, most movies have to be responsible, and say, well, in the end the id had it’s little time in the sun, but now we’re going to back to a sensible and super-ego-directed bla bla bla. And, in Animal House, we let the id win. I think people just adore that. It goes beyond being about the politics of the sixties, even though it was to some extent about that. And that’s why, thirty years later, people are still loving it the way they do. It’s not about the sixties any more.

M: Right.

C: Of course, with the government we’ve had recently, there’s been some similarities.

M: Yeah. Maybe good timing for your book, then.

C: I hope so, Mark.

M: Great. Well, thanks, Chris.

C: Okay, man. You’re welcome.

The Real Animal House is available at Amazon and other fine book retailers.

Real Animal House Book Now Available

November 14, 2006 | Permalink | Comments: None »

Chris Miller’s book, The Real Animal House, is out now and seems to be doing well. Two things: First, Chris is going to appear tonight on The O’Reilly Factor on Fox News. Update: Chris’s interview on The O’Reilly Factor was bumped for another story and may appear later this week. Stay tuned or check Chris’s website. Second, I conducted a phone interview with Chris yesterday about the book and other stuff. I will post the transcribed interview here as soon as I can (within the next day or so, I hope).

In Animal House news…

August 21, 2006 | Permalink | Comments: None »

It looks like Chris Miller has written a book, which will be out in November, called The Real Animal House. It appears to be about the real frat house that the movie and his “Adelphian Lodge” stories were based on.

Mark's Very Large Plug. You might think, as you wade through this site, that I have no life. Not true. I spend about two days a year working on Mark's Very Large National Lampoon Site. The rest of the time I make fonts. You can see my real website here. I also have an “art” website where I post caricatures and other stuff. For Lampoon-related stuff and site updates, follow me on X (Twitter). Also, check out my YouTube channel, where I post videos related to National Lampoon.

Original material (excluding quoted material) © 1997-2024 Mark Simonson.

Mark's Very Large National Lampoon Site is not affiliated with National Lampoon or National Lampoon Inc.

Click here for the real thing.