National Lampoon Revisited event video has been posted on FORA.tv. If you missed the event, You can see it now. (Thanks to Matthew for the link.) Update: This video is unfortunately no longer available. But you can see some video I shot at the event here.

National Lampoon Revisited Video Online

December 15, 2010 | Permalink | Comments: None »

National Lampoon Event Reactions

December 7, 2010 | Permalink | Comments: None »

I’m still working on my write up about last Saturday’s event. In the mean time, you can read Dennis Perrin’s take on it. (Dennis wrote the biography of Michael O’Donoghue, ” Mr. Mike: The Life and Work of Michael O’Donoghue, The Man Who Made Comedy Dangerous“.)

2/9/16 Update: So, I never got round to posting my write up. It was really, really cool to be there, and probably the most amazing thing to happen with me as a result of doing this website, but I didn’t really know what to write. I may get around to it someday, but it’s like more than six years later now as I write this update. Do you really care? You do? Well… Maybe I’ll get to it. In the mean time, take a look at the next news item, which has a link to a video of the event. It’ll be almost like you were there…

10/19/23 Update: I finally wrote about it here. Also, Dennis Perrin has apparently removed his post about the event from his blog.

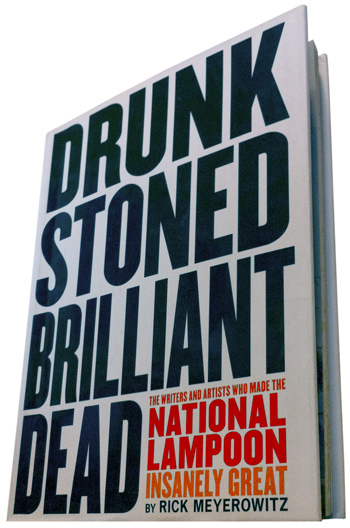

Reviews Coming in for Drunk Stoned Brilliant Dead Book

December 6, 2010 | Permalink | Comments: None »

While you’re waiting for me to post my item about Saturday’s event, here are some reviews of Drunk Stoned Brilliant Dead:

And, to show it’s not just New Yorkers writing about it, here’s one from Saginaw, Michigan: The Review

National Lampoon Revisited—Post Event

December 6, 2010 | Permalink | Comments Off on National Lampoon Revisited—Post Event

National Lampoon Revisited at the New York Public Library was almost everything I hoped it would be and more. I will post something about it here soon. One thing: The NYPL posts videos of events like this on the its site on this page. There were video cameras there, so, presumably, this one will be, too. I’ll post a link when and if it becomes available.

Update: So, I never got around to posting something. Sorry. Okay, here it is: It was fantastic. There. Satisfied?

10/19/23 Update: Never say never. Finally.

“What?” “I said there’s a banana in your ear…”

December 3, 2010 | Permalink | Comments: None »

The original painting by Mara McAfee for the November 1973 cover of National Lampoon—the one that looks like a self portrait of Vincent Van Gogh with a banana in his severed ear—is up for auction. If you’re interested, there’s more info here. Update: It sold for $7,320 a week or so later.

NYPL Live National Lampoon Event in Ten Days

November 24, 2010 | Permalink | Comments: None »

A week and a half from now (December 4), a bunch of former NatLamp people are getting together at the New York Public Library to celebrate the publication of Rick Meyerowitz’ Drunk Stoned Brilliant Dead. I will be there, too. More info here.

It Must be Rick Meyerowitz Month

September 30, 2010 | Permalink | Comments: None »

Someone on eBay is selling a pair of the Nixon & Agnew puppets that Rick designed for National Lampoon in 1970 (as seen on the cover of the October 1970 (Politics) issue). Check it out. (Thanks to John for the tip.)

Rick Meyerowitz on the Radio

September 29, 2010 | Permalink | Comments: None »

Yesterday, Rick Meyerowitz was interviewed about his new book (Drunk Stoned Brilliant Dead) on NPR’s All Things Considered. You can listen to it online here.

My Skype Call with Rick Meyerowitz

September 15, 2010 | Permalink | Comments: None »

For fans of the National Lampoon, Rick Meyerowitz‘s new book, Drunk Stoned Brilliant Dead: The Writers and Artists Who Made the National Lampoon Insanely Great, is easily the biggest thing to happen in the last 30 years.

For fans of the National Lampoon, Rick Meyerowitz‘s new book, Drunk Stoned Brilliant Dead: The Writers and Artists Who Made the National Lampoon Insanely Great, is easily the biggest thing to happen in the last 30 years.

It’s a large-format book with over 300 pages of lavishly reproduced material, mainly from the first decade of the magazine, and dozens of essays and stories written by former Lampoon writers and artists. This is the book I’ve long wished someone would write, and who better to do it than the artist who created the Mona Gorilla.

I spoke to Rick last Friday, via Skype. It didn’t take much to get him talking about the book and about National Lampoon. I had a long list of questions. I managed to ask only a few of them. Mostly I just sat back and said “yeah” every fifteen seconds and he somehow answered them all anyway….

Rick: My partner, Maira Kalman, and I were just at the printer picking up a print of our parody New York City subway map. I had this notion to replace every single name on the map with the name of a food. We wound up with “The New York City Sub-Culinary Map”. The New Yorker‘s online store is going to sell it. I was telling Sean Kelly about it the other day, and he said, you would have done this for the Lampoon if there was still a Lampoon. I said, yeah, but they wouldn’t have paid.

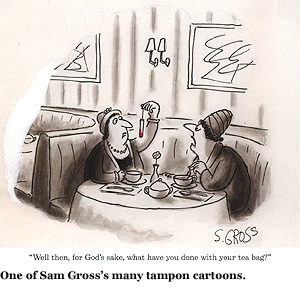

All these guys I’ve spoken to [for the book]—Ted Mann, Brian McConnachie, John Weidman—if there was a Lampoon, that would be home for their ideas. But that doesn’t mean they haven’t had Lampoon ideas. We have to water them down to publish them. You look at The New Yorker and see when they run the occasional Sam Gross cartoon how funny it is, but it’s not a Lampoon idea. His real home was at the National Lampoon.

Mark: He’s not doing tampon cartoons in The New Yorker?

Mark: He’s not doing tampon cartoons in The New Yorker?

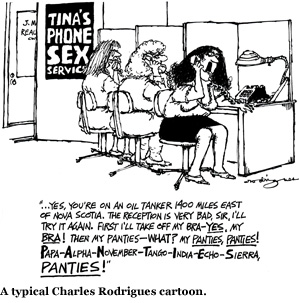

Rick: (laughs) I spoke at the Sun Valley writers’ festival a couple of weeks ago, in Idaho. I gave a talk about the book and I discovered that they’re not going to laugh a whole lot over Chris Cerf’s rather intellectual script of the “Constitutional Comics”. But when I showed that tampon cartoon by Sam Gross, people screamed their heads off. They fell out of their chairs. I loved that. And I thought, put more Sam Gross and Charlie Rodrigues cartoons in my talk.

Mark: I’m glad you put a lot of cartoons in the book. Tell me about the book.

Rick: Well, this is a book done by an artist. I waited 35 years for some writer to tell the story. And they didn’t do it. When I decided to do this book, my thought was, here’s a chance to do a book that includes the artist. The magazine really was built, in a lot of ways, around its imagery. And its imagery was fantastic. There was a team of people that were supplying those images. Like Michael Doret, who did a few things for them. Or Mara McAfee. There doesn’t appear to be any one place where you could go to find her work, and I decided not to do a chapter on her, but I thought she was really important. Did you feel I short-changed some people? Or do you think the book had balance?

Mark: There were a few people I noticed that aren’t in it, that I would have maybe liked to have seen in it, like B.K. Taylor. But I think you did a good job selecting who to include.

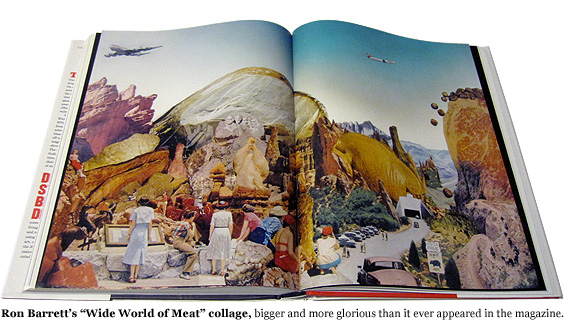

Rick: B.K. Taylor was strictly a Funny Pages artist. I was able to include Ron Barrett, for instance, because he transcended the Funny Pages. And Stan Mack, even though Mule’s Diner was in the Funny Pages, Stan did most of his work [for the Lampoon] before there was a Funny Pages. But really, the crux of the book is, these are the people that were there when the magazine was revolutionary in the 1970s.

The only two people who came aboard in the ’80s who are featured in the book are two guys who did two extraordinary pieces, one by Ron Hauge, which is his “Rejected New Yorker Covers”, and the other is by Fred Graver, “Tintin in Lebanon”, which is so extraordinary. When I read that, a few years ago, Bush was president, we were buried in Iraq, and I thought, oh my god. This is Iraq. All these Arabs running around, blowing each other up, and blowing us up. I thought, I have to include this.

Then, of course, Fred wrote a great essay for the book about Sean Kelly, which is one long joke about “the bear”, which I thought was really funny. And it includes a quote which I asked Sean about the other day at lunch. It was around Sean’s table that Fred first heard, “Someone oughta take that fucking Mother Teresa down a peg or two.” (laughs) I said to Sean, does that ring any bells for you? He says, “Oh, yes. That was said.” (laughs) These angry Catholic boys, is what they are. Sean said the other day, nobody hates the church or the representatives of the church more than we ex-Catholic boys. And that was who the Lampoon was, you know, at the beginning. A lot of pissed off Catholic boys.

Mark: I remember noticing that when I’d been reading for a year or so. I’d read Mad magazine when I was younger, and it had a somewhat different socio-economic background to it. There were more Jewish and Italian writers. The tone at the Lampoon was different. And I think it was that Irish Catholic influence. I didn’t know what it meant exactly, being a midwestern teenager.

Rick: Well, I can tell you that when Harvey Kurtzman in the early ’50s began Mad magazine, Harvey came out of that immigrant milieu, although he of course was born in New York City, where everybody had an accent. Where ethnicity was not a dirty word. And there was a very ethic sense to that humor in Mad. There were all those words, like “furshlugginer”. It’s a Yiddish word. They brought that out into the culture as part of their natural way of thinking about the world. A generation later, these Harvard boys, and these other very bright boys, who came to begin the Lampoon, were not thinking in those terms. They were coming from a whole different direction. There were very few jews, except maybe some freelancers, at the Lampoon until later years. Gerry Sussman, for instance came in ’73. And, you know, I loved them for it. I’d never heard stuff like that.

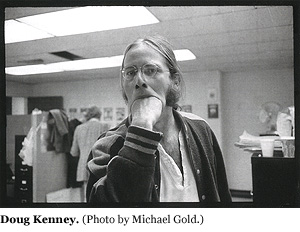

Even though it made fun of many things, there was real literacy behind the Lampoon. To paraphrase P.J. O’Rourke, who wrote about Doug Kenney, he said, Doug was primarily smart, not primarily funny. You can say that about everybody at the Lampoon. These were primarily smart guys. This was a literary enterprise. This was not just a, you know, tits and ass magazine that it became later on. Of course, it had its share of naked women in it, in part because Matty Simmons was insistent on it. The other part was, that’s kind of funny to a bunch of ex-frat boys.

Even though it made fun of many things, there was real literacy behind the Lampoon. To paraphrase P.J. O’Rourke, who wrote about Doug Kenney, he said, Doug was primarily smart, not primarily funny. You can say that about everybody at the Lampoon. These were primarily smart guys. This was a literary enterprise. This was not just a, you know, tits and ass magazine that it became later on. Of course, it had its share of naked women in it, in part because Matty Simmons was insistent on it. The other part was, that’s kind of funny to a bunch of ex-frat boys.

Mark: So, how did the book come to be? How did it start?

Rick: Well, Eric Himmel, the editor in chief of Abrams, said to me, how come you’ve never pitched me a book about the National Lampoon? He’s always asked me about the Lampoon. Apparently, I’d conveyed so much information to him that he wondered why I’d never pitched a book to him. I said, well, who am I to write a book about the Lampoon? He said, you’re exactly the right person, because you’re in touch with everybody. And your history runs all through the magazine. You have an institutional knowledge, and you have all these friends. And, as far as the artists are concerned, you have a lot of respect. He said, why don’t you make me a proposal? That’s how it happened.

I sat down at my computer and started to type a proposal. As it started evolving, much as a sketch will evolve as I start to draw, I began to see what it was I wanted to say: This is not a history of the magazine. That’s been done already. This is a book about what I really know, the writers and artists. As soon as that thought came to me, I understood how I could make a book. I have unique access. I could go to Charlie Rodrigues’s widow, and I could go to Gahan Wilson, and Sam Gross, and Randy Enos, and Stan Mack, and Wayne McGloughlin, and I could say, give me your original art. Let me have it in my house for a while. And, we’re going to make incredible photographs or scans and reproduce this stuff digitally in a way it never was before, and have it look smashing on the page.

I had stuff in my studio you wouldn’t believe. I had Ron Barrett’s “Wide World of Meat”, that giant collage. It’s big. Too big to scan. I had to take it out and have it photographed. I thought, that’s gotta be in the book. Tony Hendra said, why isn’t that in my chapter? Because he’s a friend of almost 40 years, I was able to put an arm over his shoulder and say, you got a big enough chapter, Tony, why don’t you share something with Ron? (laughs) I pointed out to him, gently, that it was Ron’s idea. He brought the art to Tony and Tony said, let’s do an article about meat. But Ron did the collage first. And after all, it does say “The Wide World of Meat, by Tony Hendra”. It just happens to be in Ron’s chapter. And he was okay with that.

So, I was able to go to all these guys that I’ve maintained friendships with. And get their original art. I was able to get their permission to use pieces they owned. I was able to get them to write things for me. I went to Montreal and visited Michel Choquette, and I got the Hitler article [“Stranger in Paradise”]. Not only did I get the Hitler article, I got the outtakes, which was amazing, and I used several of them. If you compare the Hitler article as it’s reproduced in the book with the one that was reproduced in the magazine, you’ll see there’s an extraordinary difference. I felt that was one of the rare failures of design in the magazine, that Michael Gross didn’t capture what a travel magazine would look like, which is what they were trying to do. It was printed on black. The whole thing looked murky, and kind of cheap instead of glorious. I told Michel from the very beginning, that I want to repurpose this article. I want to take the article and make it look like a modern travel magazine article, and make it glow with digital reproduction in a way that it never did in the Lampoon. But the text would be the same, though we added a few lines of text because for the new photos in there, like Hitler getting a haircut.

Mark: Yeah. The reproduction was typical for a mass-market magazine at the time. They did do some really interesting things with the printing, like using different paper stocks and things like that. But you’re right, the quality you can get now is way beyond what they were able to do back then.

Rick: Right. I always expected my work to look lousy. The color looked greasy to me. Much greasier than it really was. So, I had a chance to use digital reproduction on my work and rescan all my originals and put them in there and make them look somewhat better. So, just being who I was in the history of the magazine, I had the credibility to go to the artists, and not be somebody they’d never heard of, saying, can I have your original art, I’m doing a book.

Mark: You’re the perfect person to do it.

Rick: This was a labor of love. This was about a time in my life and about a group of people I loved being part of, and about work that I loved doing. Maybe the best work I ever did. I don’t expect to make a lot of money from this book. The best thing that’s going to happen with me here is reconnecting with everybody else, and maybe the next book will be a little easier to sell because I’ve got credibility from this book. I didn’t do this book as a money maker. I didn’t quite understand that when I got into it, because I didn’t know how long it was going to take me. Now I know. (laughs)

Mark: Well, I hope you’re wrong about not making money from the book. Did you have a particular audience in mind?

Mark: Well, I hope you’re wrong about not making money from the book. Did you have a particular audience in mind?

Rick: I wrote this book for the 35 people I profiled in the book, including the dead ones. I wrote this book for Doug Kenney. I wrote this book for Gerry Sussman. I wrote this book for Sean Kelly. And I wrote it for Charlie Rodrigues. I wrote this book for me. This is a book about us, that small group. But I also wrote it for you. I wanted this book not to be an exercise in nostalgia or to be sentimental. I wanted this book to be modern. I wanted it to look sharp in the book store. I wanted a cover that was not that fucking dog with the gun to its head.

Mark: (laughs) Thank you for that.

Rick: Am I tired of that, or what? It was a clever idea, but… There is somebody doing a documentary—didn’t you write about this on your site?—they want to call it “Watch This Movie Or We’ll Kill This Dog”. Can’t they get over it? That is so antithetical to Lampoon humor, that they can’t come up with another title except that same thing over and over. Pathetic. I wanted a book that was designed in a modern way and felt new. I would like people to see how relevant Lampoon humor is now. How it transcends beyond the war in Vietnam, to what’s going on in Iraq and Afghanistan. How almost nothing has changed in the world when there’s mention of the environment. There’s several in the book. One wonderful little piece in the “News of the Month” by Henry Beard about a slick of clear salty liquid being found off the coast of California. I read some of that stuff and I though, Jesus, nothing’s changed here. I want it to feel contemporary. I want a contemporary audience. So, yes, I want some of the readers of The Onion. But not just the readers of The Onion. I want young people who are reading The New Yorker—smart people—to see this. But in my heart, I was making it for those people who were the core of the magazine. Today I had an email from Danny Abelson, who received his book yesterday, saying how moved he was, how smashing it was, how great it looks, I feel really great.

Mark: That’s one of the things I wanted to ask about. What’s been the reaction to the book by people who’ve seen it?

Rick: Here’s a few [Rick sent these later via email]:

“I have seldom been more moved with sweet nostalgia than during our page by page study of your book DRUNK STONED BRILLIANT DEAD we took in that sunny restaurant by the sea. The sight of those dear young things we used to be bravely taking on the universe moved me deeply from scalp to toes, chilled me to the bone, warmed my heart and near made me weep—then and there in front of you both—with the profound gratitude I’d had the extraordinary good fortune to have been there and done that.

“What a marvelous bunch we were and how proud I am to have the good luck to have been one of those brave young things in the LAMPOON’s sword swinging frontal attack on the stupidity that so plagues our species! I only wish our bold campaign had met with more success.” —Gahan Wilson

“The book is most impressive, a huge accomplishment. Thank you for your kind words. It’s fascinating, and rather overwhelming to see all these people together, then and now. I’ve only just started to read each segment but have a great sense of nostalgia for these folks, the magazine, even for the times.” —M.K.Brown

“It vibrates with energy.” —Brian McConnachie

“Rick its a masterpiece, and in no small part because of your writing (as well as editing). You did a beautiful job of putting everything in historical context. I like the consistently friendly tone of your writing that makes one feel like they were there, and I love the personal connection to all involved. It’s oh, so well told. I can’t imagine anyone doing a better job than you have done.” —Michael Gross

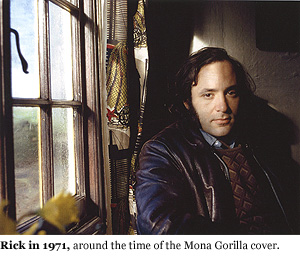

Mark: My very first impression of National Lampoon was seeing your Mona Gorilla painting on the cover of the first “Best Of” anthology back in ’72. Later on, I sent for the poster, too. Which I still have. What’s the story behind that painting?

Rick: In the book, I tell a story about how I came up with it. In my chapter, under my photo, taken in 1971, same year as Mona Gorilla. It’s color-coordinated with Mona Gorilla, which I found humorous. Henry and Doug came down to my loft in Chinatown. We were going out to have a Chinese meal. And, by the way, I usually paid. I always appreciated the notion that these (in later years) two millionaires were borrowing $5 from me. And I happen to be a guy who’s on social security. And you can print that. (laughs)

Rick: In the book, I tell a story about how I came up with it. In my chapter, under my photo, taken in 1971, same year as Mona Gorilla. It’s color-coordinated with Mona Gorilla, which I found humorous. Henry and Doug came down to my loft in Chinatown. We were going out to have a Chinese meal. And, by the way, I usually paid. I always appreciated the notion that these (in later years) two millionaires were borrowing $5 from me. And I happen to be a guy who’s on social security. And you can print that. (laughs)

We were talking, and they said, we want you to do a cover. I said, what’s in the issue? Doug said, I’m doing this piece on the “undiscovered notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci. It would be funny to have something by da Vinci. I said, how about “The Mona Gorilla”—the “Mona Lisa” as a gorilla. I blurted it out, Mark. I just blurted it out. There was no thought. I didn’t say, let me think a minute. It was just a bunch of guys sitting around, bottles of beer in their hands, bullshitting. They started laughing. And I thought, it’s too sophomoric. It sounds stupid. They said, no, you’re doing it. And they talked me into it. Can you imagine? I almost talked myself out of it. You want to know the dirty little secret of the Mona Gorilla? I’m gonna tell you right now. She’s an orangutan.

Mark: You know, you’re right. I’m looking at it right now. And you’re right.

Rick: She’s Mona Orangutan. I don’t go into that very often.

Mark: Well, I’m glad they talked you into it.

Rick: Maybe the impulse to initiate it was from a writer, from two writers who were geniuses, but the idea for the cover came from an artist. And they trusted the artist with the idea. You know, I worked for Harvey Kurtzman a few times. He got into the drawing with you, as if he got into your pants with you when you were trying them on. It was annoying. Make the eye like this, have the finger pointing this way. Do this, do that. It got to be too much. Harvey was a genius, and got great work out of some artists at Mad magazine, but I couldn’t work that way.

The great thing about Doug Kenney and Henry Beard—Gahan Wilson will tell you the same thing. They would call Gahan and say, Gahan, the theme is “back to school”. You have six pages. Goodbye. He never turned it in and said, how’s this? How about if I do that? They said, do what you want. We trust you. You’re Gahan Wilson. We’re proud to have Gahan Wilson in our magazine. Gahan told me he never had that kind of relationship at Playboy, and he’s been at Playboy for 54 years, or whatever it is.

The talents that worked on this magazine were not primarily funny, they were primarily smart. The only fight I had about something in this book was about Henry Beard’s monumental, gigantic “Law of the Jungle”, which no one will ever read. I read that thing and I thought, this is a work of genius. This has to go in the book. How am I going to include the twelve pages of this work without killing the book. I managed to do it. I decided that would be the only thing of Henry’s in his chapter. The reason I included it in full is to make a point. That this was a place where a man could do twelve pages of a law brief, that looks like it was written as a Supreme Court brief, and that it was okay. Somebody could do it. And not only could do it, but could do it brilliantly, and knew how to do it. Louise Gikow—she was the copy editor on that—says, he wrote it in three languages, English, Latin, and Legalese. It takes your breath away. John Weidman, who would write a parody of the New York Bar Exam, and who used to sit in class at Yale Law School between Bill Clinton and Clarence Thomas, wrote the article [Law of the Jungle], but Henry rewrote it, and rewrote it much better than John could ever have done. Henry didn’t go to law school. Henry was just brilliant. So, I wanted to say, here’s this piece. Look what they were capable of. Look how smart they were. Look how literate they were. Look how contemporary this stuff is. That’s what I’m trying to say in this book. That’s why that fucking dog is not on the cover.

The talents that worked on this magazine were not primarily funny, they were primarily smart. The only fight I had about something in this book was about Henry Beard’s monumental, gigantic “Law of the Jungle”, which no one will ever read. I read that thing and I thought, this is a work of genius. This has to go in the book. How am I going to include the twelve pages of this work without killing the book. I managed to do it. I decided that would be the only thing of Henry’s in his chapter. The reason I included it in full is to make a point. That this was a place where a man could do twelve pages of a law brief, that looks like it was written as a Supreme Court brief, and that it was okay. Somebody could do it. And not only could do it, but could do it brilliantly, and knew how to do it. Louise Gikow—she was the copy editor on that—says, he wrote it in three languages, English, Latin, and Legalese. It takes your breath away. John Weidman, who would write a parody of the New York Bar Exam, and who used to sit in class at Yale Law School between Bill Clinton and Clarence Thomas, wrote the article [Law of the Jungle], but Henry rewrote it, and rewrote it much better than John could ever have done. Henry didn’t go to law school. Henry was just brilliant. So, I wanted to say, here’s this piece. Look what they were capable of. Look how smart they were. Look how literate they were. Look how contemporary this stuff is. That’s what I’m trying to say in this book. That’s why that fucking dog is not on the cover.

Mark: Thanks, Rick.

Drunk Stoned Brilliant Dead: The Writers and Artists Who Made the National Lampoon Insanely Great is out now and available at all reputable (and some not-so-reputable) book stores, online and off.

NatLamp CEO Sentenced

September 10, 2010 | Permalink | Comments: None »

National Lampoon CEO, Dan Laikin, was sentenced to 45 months for stock manipulation (link to story). (Thanks, Dave, for the tip!)

Mark's Very Large Plug. You might think, as you wade through this site, that I have no life. Not true. I spend about two days a year working on Mark's Very Large National Lampoon Site. The rest of the time I make fonts. You can see my real website here. I also have an “art” website where I post caricatures and other stuff. For Lampoon-related stuff and site updates, follow me on X (Twitter). Also, check out my YouTube channel, where I post videos related to National Lampoon.

Original material (excluding quoted material) © 1997-2024 Mark Simonson.

Mark's Very Large National Lampoon Site is not affiliated with National Lampoon or National Lampoon Inc.

Click here for the real thing.